What Are Some Negative Effects That Chronic Pain Can Have on the Pediatric Population?

- Review

- Open Access

- Published:

Psychosocial perspectives in the treatment of pediatric chronic pain

Pediatric Rheumatology volume 10, Article number:xv (2012) Cite this article

Abstract

Chronic pain in children and adolescents is associated with major disruption to developmental experiences crucial to personal aligning, quality of life, bookish, vocational and social success. Caring for these patients involves understanding cognitive, melancholia, social and family dynamic factors associated with persistent pain syndromes. Evaluation and handling necessitate a comprehensive multimodal approach including psychological and behavioral interventions that maximize render to more developmentally appropriate physical, bookish and social activities. This article will provide an overview of major psychosocial factors impacting on pediatric pain and disability, suggest an explanatory model for conceptualizing the development and maintenance of hurting and functional disability in medically difficult-to-explain pain syndromes, and review representative bear witness-based cognitive behavioral and systemic treatment approaches for improving operation in this pediatric population.

Review

Background

It has been estimated that fifteen to xxx percent of children and adolescents feel chronic pain, with prevalence increasing with historic period and occurring slightly more than unremarkably in girls than boys [i, 2]. Pain is considered a chronic status when it has persisted for at to the lowest degree three months, moving beyond simple tissue impairment (nociceptive) to subsequent changes inside the peripheral and central nervous systems (neuropathic). The experience of chronic pain is too impacted by psychosocial factors (stress, negative affective states, family response, etc.) in add-on to these biological factors [3]. The near unremarkably reported locations of pain in children and adolescents are the caput, stomach, arms and legs. The about common chronic hurting conditions in children include migraine, recurrent abdominal pain, and general musculoskeletal pain [ii]. Symptoms of pediatric chronic pain can be severe and disabling, impairing the daily performance of children and having an adverse touch on on their families. Therefore, information technology is paramount that these chronic conditions be accurately assessed and treated in lodge to improve functioning and prevent long-term sequelae and deviation from a normal developmental trajectory [3, four].

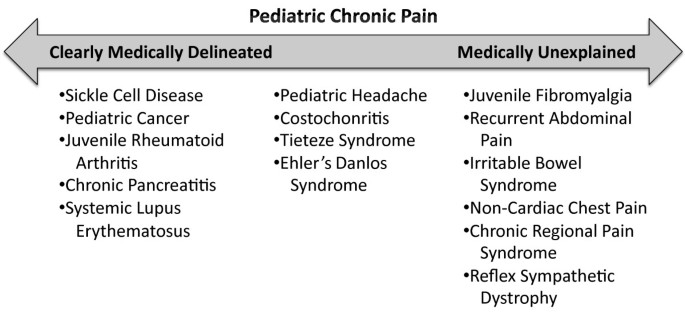

There are a wide variety of medically hard-to-explain chronic painful conditions that present in the pediatric population, which are frequently referred to as medically unexplained syndromes (MUS) [five]. These include such conditions equally juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome (JFMS), chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), widespread hurting syndrome (WPS), chronic pelvic pain, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), recurrent abdominal pain (RAP), tension headaches, noncardiac breast hurting, circuitous regional pain syndrome (CRPS), reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), amid others. Central to these weather condition is a broad discrepancy in the actual tissue harm sustained by a patient, the perceived severity of the status, and the degree of disability exhibited. Alternatively, patients with more clearly delineated medical disorders, e.g., babyhood leukemias (east.1000., ALL, AML), juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), sickle prison cell affliction (SCD), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), to mention some of the major illnesses, oft experience limitations in their daily functioning due to the effects of debilitating pain and accompanying fatigue and/or the side effects of handling. Lastly, there are those painful pediatric weather condition which do non fall neatly on either terminate of the continuum with regard to how well an organic explanation fits the patient'southward reported level of hurting or disability, e.g., certain headache variants, costochondritis, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Tietze syndrome, to give some examples (see Effigy 1). The current review volition focus primarily on psychosocial approaches to the treatment of the medically hard-to-explain chronic painful atmospheric condition.

Continuum of painful atmospheric condition.

In medically unexplained hurting syndromes (MUS) it has been suggested that the pain, fatigue, and functional limitations associated with these conditions may exist due, at least in function, to abnormalities in centrally-mediated processing functions rather than damage or inflammation of peripheral structures [5]. Neuroanatomically, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is frequently implicated in this process. This dysregulation, which may be triggered by infection, injury or intense physical or psychological stress, results in a malfunction of the central mechanisms that regulate pain, energy, sleep, concentration, memory, etc. [6]. More specifically, increased neural activity in the posterior insula region of the brain has been implicated as at least a component of the sensory distension seen in these patients [7]. Other fundamental nervous organisation mechanisms that may be involved in the generation and maintenance of chronic hurting include loss of descending analgesic activity and central sensitization, diminished activity of the descending serotonergic-noradrenergic system, and increased activity of endogenous opioidergic systems [seven]. Behaviorally, evidence suggests that pain and fatigue tin become classically conditioned to (associated with) certain stimuli in the surround, resulting in functional limitations when the individual is confronted with these stimuli. A number of functional imaging studies have demonstrated increased neural activity in brain structures involved in the processing of awareness, movement, noesis and emotion in patients with these conditions, as compared to salubrious controls experiencing the same stimuli [8].

Patients with these atmospheric condition often experience considerable skepticism and avoidance by health care providers due, in part, to the difficulty in assigning an accurate diagnosis. On the other paw, for the treating doc the patient'south clinical presentation may be frustrating due to the absence of a clear cutting etiological explanation, inconclusive investigative tests, and lack of well validated medical treatments. This tin can lead the physician to ascribe the patient's symptoms primarily to psychological factors. However, referral to a child psychologist or psychiatrist is oftentimes met with defensiveness and even acrimony on the part of the patient and/or family, who go on to identify a high value on finding a specific and readily remediable physical explanation. In such circumstances the patient continues to experience a lowered quality of life with reduced operation in multiple arenas critical to optimal development. This prolonged frustration of seeking a clear medical explanation and handling approach may further contribute to symptom exacerbation and feelings of hopelessness. This can prepare into motility an increased interdependency on parents and caregivers and reduced demands on the patient, that may plant a level of adaptation below the patient's premorbid baseline level. Secondary gain associated with the sick role and reduced physical activity leading to deconditioning produces further disability [9].

Psychosocial factors in pediatric pain

A biopsychosocial conceptualization of chronic pain posits a conceptual shift away from attempting to differentiate concrete from mental or emotional pain. This model acknowledges the multidimensional nature of pain in which biological, psychological, private, social and environmental variables are interactive in the development, maintenance, and subjective experience of pain and disability [10–15].

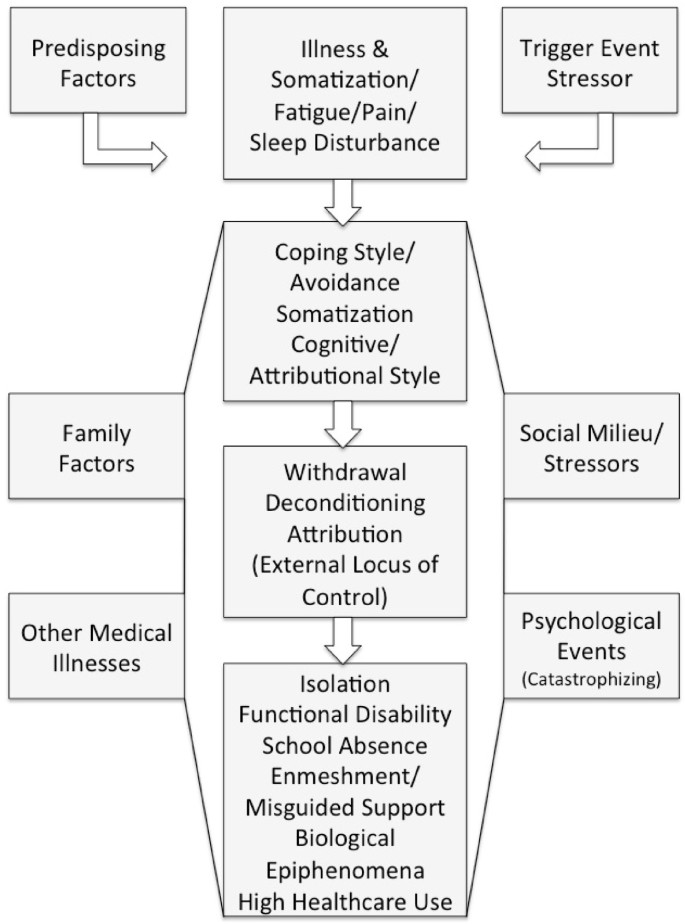

A proposed dynamic-interactive explanatory model underlying this process is presented in Figure two. This model postulates that individuals who develop these weather may have Predisposing Factors or vulnerabilities which, when combined with overt or covert Trigger Events (viral disease, psychological stress), effect in an initial Affliction with associated Somatic Symptoms including Pain and/or Fatigue and Sleep Disturbance. This may lead to the patient engaging in Avoidance of activity every bit a primary Coping Manner, Somatization (increased vigilance to concrete symptoms) and Attribution of the illness primarily toward events outside their control, i.e., External Locus of Command. Influenced by boosted events such equally Family Factors (overprotection, triangulation), Social Milieu and Stressor factors (peer relationship issues), Other Medical Illness (low grade infections, pain/fatigue exacerbations), and Psychological Events (catastrophizing cognitions), the patient may engage in farther Withdrawal, leading to Deconditioning and snowballing Increasing Attributions that their affliction/debilitation is due solely to a unitary illness procedure for which there is a unitary passive treatment (medication, surgery, etc.). The final pathological outcome is a patient who experiences increasing social Isolation, increased Functional Disability, Enmeshment with their primary caregivers, and boosted Biological Epiphenomena and High Healthcare Use that farther reinforce a somatic focus and an emphasis on finding a unitary medical "cure." The post-obit section will accost the findings of investigations supporting components of this explanatory model.

Explanatory model of chronic hurting.

Family unit factors

Chronic pain has an adverse impact on the overall quality of life for both the child and the family [16], leading many to endorse a stress appraisal and coping model in which child disability and family dynamics are a function of the kid and family interpretation of symptoms, type of coping employed and parental supportive efforts [9, 14, 17, xviii]. For some families the child's hurting symptoms may play a functional role inside family interaction patterns and relationships [xix–23]. More solicitous parental responses to pain behaviors (east.g., caregivers' sympathy, attending to symptoms, emotional reactions, modeling of symptoms, and reinforcement of pain behavior via avoidance of responsibilities) have been associated with greater pain, ill role behavior and functional disability, contained of stress level or hurting intensity [24–34]. In a study of children with chronic functional intestinal hurting, when parents attended to symptom complaints, their children exhibited nearly twice as many such complaints [35]. Table1 gives examples of family dynamics that are oft observed in patients with chronic hurting.

Coping, cerebral style and personality factors

For children suffering from painful medical conditions, the level at which they are able to office is influenced by a number of individual and systemic factors including child and family unit interpretation of pain symptoms, blazon of coping employed, and parental attempts to back up their child'southward efforts to cope with the hurting [15, 17, 18]. Children with chronic pain have been plant to possess too few and ineffective coping strategies and portray themselves every bit having a lack of control over many aspects of their symptoms [36, 37]. Claar, Walker and Smith [38] found pain and functional disability to exist more than common in pediatric patients with lower perceived competence in academic, social and athletic arenas, and pain-related inability to be reinforced if information technology allowed the private to avoid activities at which the kid believes him/herself to be ineffective or unsuccessful. Additionally, these children exhibited a tendency towards perfectionism and setting exceedingly loftier expectations [38]. In contrast, children who employ more agile coping strategies report a greater sense of control and display less pain beliefs, social withdrawal and functional inability [39, 40]. Negative emotions (feet, low) and poor emotional regulation have been found to be associated with greater functional disability [7, 41–44]. Furthermore, regardless of the perceived hurting severity, when children regard their hurting to be a serious health-threatening condition and their coping ability to be low, their pain tolerance is lower.

Children with chronic pain have been observed to report greater pain behavior if they exhibit a cognitive design of "catastrophizing," i.eastward., a cognitive style characterized by increased focusing on hurting and exaggerated/fearful appraisals of hurting symptoms and their consequences. This cognitive fashion is associated with increased pain severity, lower pain tolerance, greater functional disability, more feet and depression, and increased apply of analgesics [45, 46]. The presence of learning disabilities, unrealistic goals in a high-achieving perfectionistic child, early on pain experiences, a passive or dependent coping mode, marital problems in the home, and chronic affliction in a parent have been shown to exist associated with visceral pain-associated inability [47]. Clinically, patients experiencing meaning functional disability associated with pain have been establish to manifest some of the post-obit qualities: extreme conscientiousness, obsessiveness, sensitivity and insecurity; broken-hearted with a tendency to ready high standards of accomplishment resulting in placing considerable stress on themselves; family members who may tend to impose loftier academic and behavioral standards [11, 48].

Slumber

Slumber disturbance is prominent in pediatric patients with chronic conditions, peculiarly when pain is involved [49–55]. Equally a issue, resolution of sleep disturbances plays an of import role in the recovery process [fifty]. The relationship between hurting and slumber is bidirectional, i.e., bereft or disrupted slumber may increment the level of hurting experienced and chronic hurting increases the likelihood of sleep disruption [56]. While the machinery responsible for this relationship is not clearly understood, information technology may exist due to a disrupting effect on emotional regulation, attention and behavioral command which impairs the teen'south ability to distract themselves from the pain sensations [56], or to neurophysiological changes that increase pain sensitivity [57, 58]. Disturbances in sleep in children have been shown to exist a major contributor to increased pain intensity, decreased health-related quality of life, and decreased performance [51, 52, 59].

Psychosocial handling components and approaches

Psychosocial treatments for chronic pediatric pain effort to address both symptom reduction and management also as reduce functional disability and improve quality of life. Such interventions are well-nigh effective when employed equally part of a multidisciplinary and interprofessional team arroyo that encourages and facilitates open up communication betwixt all health care providers and educators, including the primary intendance medico, medical specialists, physical therapists, teachers, counselors, etc., in order to orchestrate a return to more normal and developmentally appropriate activities. I or more than of these specific components may be needed in combination with pharmacological and physical exercise/therapy interventions. The particular individualized approach employed will vary dependent upon such factors every bit patient history and symptom presentation, response to previous treatments, unique family dynamics, and environmental factors (service availability, insurance coverage, etc.). Such a comprehensive multidisciplinary arroyo should be strongly considered when symptoms have become protracted and interfere in a major way with the patient's ability to function academically, socially or vocationally. The post-obit is a review of specific psychosocial intervention components that have been developed and practical to these weather condition. These have applicability to both child and boyish patient populations.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

CBT is the most well validated not-pharmacological treatment for chronic hurting in pediatric patients [60]. 1 of the primary goals of CBT is to identify and correct cognitive distortions, which, in the case of chronic pediatric hurting, may involve patient and parental beliefs about the child's affliction and such factors every bit activity restriction, affliction exacerbation, school attendance and social interest, etc., that may impede movement towards rehabilitation. CBT approaches to pediatric pain accept been shown to alter patient symptom-related behavior (attributions) and, subsequently, level of functional disability [61]. Since it has been demonstrated that negative affective states are associated with pain perception and level of functional impairment [42], CBT interventions have also targeted reductions in feet, depressive and somatic symptoms. In particular catastrophic thinking, a prime target of CBT interventions, has been associated with poorer result and greater functional disability in patients with chronic pain. Some of the major cognitive distortions targeted in treating chronic pediatric pain from a CBT approach are described in Table2. When delivered in a family unit-based treatment arroyo, CBT targets parental responses to the child's pain behaviors, leading to a subtract in reinforcement of these behaviors and increased reinforcement of improved child functioning. Several contempo event studies of psychosocial interventions with pediatric chronic pain, most involving a potent CBT component, are summarized in Table3.

In a study of 30 adolescents with JFMS randomly assigned to 8 weeks of either CBT or cocky-monitoring, those receiving CBT demonstrated significantly greater ability to cope with hurting than those in the self-monitoring only condition [62]. On follow up, subjects had significantly lower levels of functional disability and depressive symptoms compared to baseline, but those who received self-monitoring followed by CBT received the nigh benefit.

Kashikar-Zuck and colleagues [63] investigated the efficacy of a CBT intervention compared with a fibromyalgia educational (FE) program, for reducing functional inability, hurting, and depressive symptoms in 114 adolescents (anile 11 to eighteen years) with fibromyalgia. Subjects received usual medical intendance for 8 weeks, and then were randomized to eight weekly CBT or Atomic number 26 sessions with two "booster" sessions. Baseline, eighth week of treatment, and half-dozen-month follow-upward issue measures were obtained. The investigators establish that almost 88% of participants completed the treatment protocol. Patients from both groups had significantly reduced functional disability, hurting, and depressive symptoms. However, CBT was significantly better than Fe for reducing functional inability. Both groups had a clinically significant reduction in depressive symptoms, and by the end of the study, the mean scores were in the not-depressed range. However, neither group attained a clinically meaning reduction in pain.

Credence and commitment therapy (Human action)

Act, is a specific cognitive behavioral approach targeting belief systems in patients suffering from chronic and recurrent painful weather, has been found to be benign for improving perceived functional ability, pain intensity, fear of re-injury, pain interference, and general quality of life [64–66]. Human activity differs from traditional CBT approaches to pain management in that the patient learns to take pain and abandon a master focus on alleviating pain and the related negative sensations and experiences with which information technology is associated. Instead the emphasis of treatment is on promoting engagement in meaningful and valued experiences and life involvements. This is accomplished via identifying and gradually exposing the child to valued activities such every bit attention school, participating in recreational activities and spending time with friends. Acceptance interventions utilize developmentally appropriate mindfulness exercises, which help with accepting unpleasant internal experiences. Handling may likewise involve cognitive externalizing interventions, east.g., characterizing painful sensations as a "hurting monster," in order to split up the experience of pain as independent from i's global sense of self [67]. ACT appears to improve patient "willingness to part" in spite of pain, anxiety and the potential negative concrete consequences of pain.

Hypnosis

Clinical hypnosis has a long history as a valuable treatment component with children with chronic hurting [68, 69], with neuroimaging studies demonstrating its efficacy in activating brain functions known to be involved in the processing of the pain feel [70]. Such hypnotherapeutic interventions as visual imagery, hypnoanesthesia, distancing and lark techniques, and reframing likely modify the child's experiencing and interpretation of the sensations associated with pain. A controlled clinical trial of hypnotherapy demonstrated efficacy over standard medical intendance with supportive therapy in reducing pain intensity and frequency in a group of 8 to 18 yr olds with recurrent abdominal pain or irritable bowel syndrome [71].

Graduated exercise and action

Increased physical activity and graduated exercise (GE) are a disquisitional component to recovery from pediatric atmospheric condition involving functional disability and pain [72]. A decrease in expectations for concrete activity and associated responsibility has been associated with less favorable v-twelvemonth result in adolescents with chronic fatigue and hurting [73], and adolescents with significant functional disability associated with their fatigue and pain have been establish to take higher levels of parental restriction from activity than their peers with juvenile arthritis [74].

Graduated practice serves to reverse the furnishings of physical deconditioning experienced by many children and initiates the process of "re-regulation," via desensitization of the fright of the physical consequences of overexertion and learning to tolerate temporary discomfort in exchange for later improvement. In improver, increased activity enhances self-conviction regarding one's power to function physically and socially and serves to gainsay the forced dependency imposed by many conditions. Most GE interventions for chronic pain focus on stretching, mobility and aerobic tolerance [75]. Garralda and Chandler [76] take described GE combined with CBT every bit the near promising intervention for managing painful and fatiguing conditions in adolescents. GE has been included in a number of integrative treatment programs and is valuable in improving debilitating symptoms, sense of "wellness" and school attendance over supportive care alone [77].

Improving academic attendance and operation

Pediatric pain typically has a pregnant negative bear upon on academic attendance and performance, though patients will vary in the level of social and bookish impairment exhibited. In a study of 221 adolescents with chronic hurting, subjects missed an boilerplate of four.5 school days per month and well-nigh one-half reported a decrease in grades since the onset of their pain status [78]. Long-term follow-upward studies accept shown that poorer academic performance and omnipresence tin have lasting negative consequences on an adolescent'southward engagement in college-level higher education and employment [79].

Active efforts at school reintegration should be a central component in the treatment of pediatric chronic pain. School systems vary widely in their receptiveness to recommended accommodations and interventions. Therefore, it is important to get familiar with the advisable federal and state regulations and statutes that apply to pediatric hurting atmospheric condition, such as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Human action (IDEA) and Department 504 of the Rehabilitation Act and the Americans with Disabilities Human activity, which require accommodations and modifications be made so that the student can fully participate in the classroom and maximally benefit from educational instruction.

Slumber intervention

Resolution of slumber disturbances plays an important role in the treatment of chronic pediatric hurting. Slumber disturbance lonely predicts lower wellness-related quality of life and higher functional disability in children and adolescents with chronic hurting [80]. For example, compared to a no-handling control group, pediatric patients receiving sleep hygiene pedagogy reported a reduction in frequency and duration of migraine headache [81]. Cognitive-behavioral interventions for sleep have also been shown to improve symptoms and quality of life in adolescents with juvenile fibromyalgia [50]. Intervention for slumber involves identifying poor slumber hygiene patterns and implementing strategies to ameliorate sleep regulation. Such strategies include: establishing a regular bedtime routine and sleep schedule, eliminating or limiting daytime naps, limiting caffeine intake, increasing morning sun exposure, discontinuing potentially stimulating activities such as goggle box/reckoner/video games, etc., within 30 min of bedtime, establishing a good for you morning practice routine, altering sleep surroundings to be a absurd, dark, repose and relaxing space that is used exclusively for sleep. Weekly slumber logs are often utilized to tape gradual shifts in slumber patterns and to monitor and encourage improved sleep hygiene and quality.

Integrated approaches

In a meta-analytic review of twenty-5 psychological intervention trials with children and adolescents with chronic pain, Palermo and colleagues [82] constitute a big positive effect of psychological intervention on pain reduction at immediate postal service-treatment and follow-up. These studies included youth with headache, abdominal pain and fibromyalgia. Less robust effects were establish for improvements in disability and emotional functioning. CBT, relaxation grooming, and clinical biofeedback all produced significant pain reduction, and this was truthful for self-administered besides as therapist-administered interventions.

A number of treatment studies accept integrated a combination of interventions that include CBT, behavioral, family–systems and GE components. The STAIRway to Health program (Structured Tailored Incremental Rehabilitation) incorporates several aspects of previously researched approaches [75]. Patients and parents are educated in a holistic understanding of their affliction that discourages an exclusively physical or psychological approach to understanding the illness. Educational components include explaining vicious cycles that exacerbate illness, including those of nutrition, slumber patterns, concrete deconditioning, social isolation, educational estrangement, and emotional cycles (including loss of cocky-esteem and confidence), also every bit bolstering adaptive coping strategies and re-evaluating negative attributions about the prognosis of their affliction and the future. A tailored gradual render to schoolhouse is planned, too as a gradual return to normal social action. Though sample size was somewhat small, compared to a control "pacing program" group, the adolescents in the STAIRway group demonstrated significant improvements in schoolhouse attendance, activity scores, and global health ratings by both the teen and treating clinician. Contrary to common patient and parental precautions to refrain from more vigorous and sustained physical activeness, closely monitored agile rehabilitation did not exacerbate symptoms in subjects [75].

Children's health and illness recovery program (CHIRP)

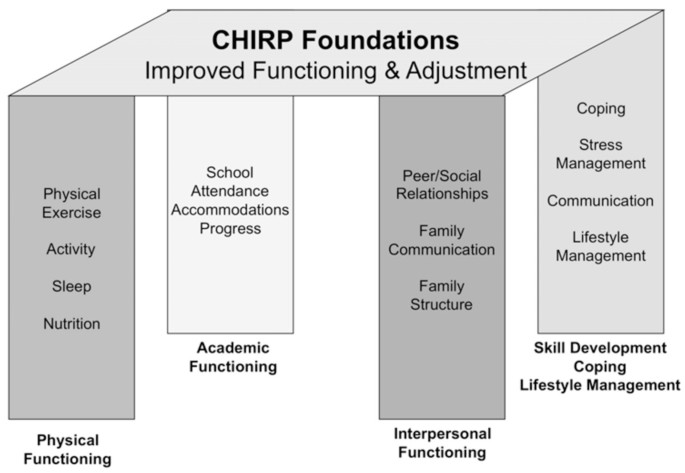

The Children's Health and Illness Recovery Program (CHIRP) is a comprehensive, multimodal outpatient intervention designed for adolescents with chronic painful and fatiguing weather condition (Carter, Kronenberger, Bowersox, Hartley, Sherman: Children's wellness and illness recovery program clinician's handbook, unpublished). CHIRP employs a 12-session manualized treatment protocol integrating many validated treatment components in a workbook format, including family unit-based CBT. CHIRP activities are designed to assistance patients in multiple areas including: ane) medical treatment adherence and related lifestyle modifications, 2) identifying and managing stress, iii) improving active coping, fourth dimension direction and problem-solving skills, 4) improving assertive communication and interpersonal relationships, 5) utilizing relaxation and self-soothing behaviors, 6) enhancing functional independence and communication in the context of the patient's family, and 7) advocating for advisable educational accommodations. The CHIRP model (see Figure 3) encourages regular advice among patient, family, wellness intendance providers and schoolhouse officials, to facilitate render to school and more than normal social functioning. Preliminary clinical result data on subjects who completed all sessions demonstrated meaning parent- and patient-based ratings of improvement in functioning and reduced pain and fatigue in adolescents with painful and fatiguing illnesses [83].

CHIRP handling model.

Inpatient handling for pediatric chronic pain

Multidisciplinary inpatient treatment programs designed to initiate more than typical childhood performance in patients with chronic hurting may be indicated for more astringent cases that are not-responsive to outpatient interventions. A study of 200 children and adolescents with chronic pain demonstrated the benefits of inpatient multimodal treatment [84]. A multidisciplinary team of pediatricians, clinical psychologists, psychiatrists, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and social workers conducted the 3-week inpatient treatment. Behavioral wellness treatment consisted of individual, family unit, and group therapy sessions incorporating cognitive behavioral principles and trauma-specific interventions. Adjunctive physical therapy, art therapy and medications were also provided. Participants received educational services during the day to promote school reintegration. Iii-month and 12-month post-treatment assessment revealed a meaning decline in hurting intensity, pain-related disability, school absence, and pain-related coping. Participants reported a 60% reduction in use of analgesics at one-year post treatment [84]. The rarity and high cost of such programs reduces accessibility for most patients and may not be appropriate for those who are less impaired and higher functioning. Multimodal outpatient handling options may be more than suitable for these children.

Conclusions

Comprehensive treatments for pediatric chronic hurting demand to include attending to psychosocial factors that are associated with and perpetuate symptom persistence and contribute to functional morbidity. There is a growing body of bear witness-based literature supporting interventions based upon cognitive, behavioral, family- and social-systems models in improving patient symptoms, quality of life and overall functioning. Future studies demand to farther investigate these treatments compared to more standard medical interventions alone, as well as efforts to brand these interventions more than accessible via such mechanisms as digital and spider web-based tools [85].

Abbreviations

- JFMS:

-

juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome

- CFS:

-

chronic fatigue syndrome

- WPS:

-

widespread pain syndrome

- IBS:

-

irritable bowel syndrome

- RAP:

-

recurrent abdominal hurting

- CRPS:

-

complex regional pain syndrome

- RSD:

-

reflex sympathetic dystrophy

- POTS:

-

postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

- ALL:

-

acute lymphocytic leukemia

- AML:

-

acute myeloid leukemia

- JRA:

-

juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

- SCD:

-

sickle cell disease

- SLE:

-

systemic lupus erythematosus

- MUS:

-

medically unexplained hurting syndromes

- HPA:

-

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

- PADS:

-

pain-associated disability syndrome

- CBT:

-

cerebral-behavioral therapy

- FE:

-

fibromyalgia educational

- ACT:

-

acceptance and commitment therapy

- GE:

-

graduated practice

- IDEA:

-

Individuals with Disabilities Education Human activity

- STAIRway:

-

Structured Tailored Incremental Rehabilitation

- CHIRP:

-

Children'due south Health and Illness Recovery Program.

References

-

Perquin CW, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AJM, Hunfeld JAM, Nohnen AM, van Suijlekom-Smit LWA, Passchier J, van der Wouden JC: Pain in children and adolescents: a common experience. Pain. 2000, 87: 51-58. x.1016/S0304-3959(00)00269-4.

-

Huguet A, Miro J: The severity of chronic pediatric pain: an epidemiological report. J Pain. 2008, 9 (3): 226-236. 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.10.015.

-

Leo RJ, Srinivasan SP, Parekh S: The function of the mental health practitioner in the cess and treatment of child and adolescent chronic pain. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2011, 16 (1): 2-viii. 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2010.00578.10.

-

Jones JF, Nisenbaum R, Solomon 50, Reyes M, Reeves WC: Chronic fatigue syndrome and other fatiguing illnesses in adolescents: a population-based study. J Adolesc Wellness. 2006, 35: 34-xl.

-

Johnson SK: Medically unexplained disease: gender and biopsychosocial implications. 2007, American Psychological Association, Washington DC

-

Gaab J, Huster D, Peisen R, Engert 5, Heitz V, Schad T, Schurmeyer Thursday, Ehlert U: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis reactivity in chronic fatigue syndrome and health under psychological, physiological, and pharamacological stimulation. Psychosom Med. 2002, 64 (vi): 951-962. 10.1097/01.PSY.0000038937.67401.61.

-

Lee YC, Nassikas NJ, Clauw DJ: The role of the primal nervous system in the generation and maintenance of chronic pain in rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011, 13: 211-ten.1186/ar3306.

-

Apkarian AV, Thomas PS, Krauss BR, Szevernyi NM: Prefrontal cortical hyperactivity in patients with sympathetically mediated chronic pain. Neurosci Lett. 2001, 311 (3): 193-197. ten.1016/S0304-3940(01)02122-Ten.

-

Stang PE, Osterhaus JT: Impact of migraine in the United States: information from the National Wellness Interview Survey. Headache. 1993, 33 (one): 29-35. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1993.hed3301029.ten.

-

American Pain Society: Pediatric chronic pain: a position argument from the American Pain Order. Am Pain Order Balderdash. 2001, eleven (1): 10-12.

-

Bursch B, Joseph MH, Zeltzer LK: Hurting-associated disability syndrome. Pain in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Edited by: Schechter NL, Berde CB, Yaster One thousand. 2003, Williams, & Williams, Philadelphia: Lippincott, 841-848.

-

Zeltzer L, Bursch B, Walco G: Pain responsiveness and chronic pain: a psychobiological perspective. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1997, eighteen (6): 413-422. 10.1097/00004703-199712000-00008.

-

Hyams JS, Hyman PE: Recurrent intestinal hurting and the biopsychosocial model of medical practice. J Pediatr. 1998, 133 (iv): 473-478. 10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70053-8.

-

Bursch B, Walco GA, Zeltzer L: Clinical assessment and management of chronic pain and pain associated disability syndrome. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1998, 19: 45-53. ten.1097/00004703-199802000-00008.

-

Zeltzer LK, Tsao JC, Bursch B, Myers CD: Introduction to the special issues on pain: from pain to pain-associated disability syndrome. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006, 31 (7): 661-666.

-

Hunfeld JAM, Perquin CW, Duivenvoorden HJ, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AA, Passchler J, van Suijlekom-Smit LWA, van der Wouden JC: Chronic pain and its impact on quality of life in adolescents and their families. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001, 26: 145-153. 10.1093/jpepsy/26.3.145.

-

Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Gruen RJ, DeLongis A: Appraisement, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986, l (3): 571-579.

-

Lipani TA, Walker LS: Children'due south appraisement and coping with pain: relations to maternal ratings of worry and brake in family activities. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006, 31: 667-673.

-

Covelman K, Scott Due south, Buchanan B, Rossman F: Pediatric pain control: a family systems model. Advances in pain research and therapy. Edited past: Tyler DC, Krane EJ. 1990, Raven, New York, 225-236.

-

Kopp M, Richter R, Rainer J, Kopp-Wilfling P, Rumpold Thousand, Walter MH: Differences in family unit functioning between patients with chronic headache and patients with chronic low back hurting. Pain. 1995, 63: 219-224. 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00045-T.

-

Logan DE, Scharff L: Relationships between family and parent characteristics and functional abilities in children with recurrent pain syndromes: an investigation of moderating effects on the pathway from pain to disability. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005, 30 (eight): 698-707. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj060.

-

Naidoo P, Pillay YG: Correlations amidst general stress, family unit environment, psychological distress, and pain feel. Percept Mot Skills. 1994, 78: 1291-1296. 10.2466/pms.1994.78.3c.1291.

-

Scharff L, Langan Due north, Rotter N, Scott-Sutherland J, Schenck C, Tayor North: Psychological, behavioral, and family characteristics of pediatric patients with chronic hurting. Clin J Pain. 2005, 21 (5): 432-438. x.1097/01.ajp.0000130160.40974.f5.

-

Fordyce We: Behavioral methods for chronic pain and disease. 1976, Mosby, St. Louis

-

Garber J, Zeman J, Walker LS: Recurrent abdominal pain in children: psychiatric diagnoses and parental psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990, 29: 648-656. 10.1097/00004583-199007000-00021.

-

Gidron Y, McGrath PJ, Goodday R: The physical and psychosocial predictors of adolescents' recovery from oral surgery. J Behav Med. 1995, 18: 385-399. 10.1007/BF01857662.

-

Liakopoulou-Kairis Thousand, Alifieraki T, Protagora D, Kora T, Kondyli K, Dimosthenous Due east: Recurrent abdominal pain and headache: psychopathology, life events and family functioning. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002, 11: 115-122. ten.1007/s00787-002-0276-0.

-

Payne B, Norfleet M: Chronic hurting and the family: a review. Pain. 1986, 26 (1): one-22. x.1016/0304-3959(86)90169-vii.

-

Schanberg LE, Anthony KK, Gil KM, Lefebvre JC, Kredich DW, Macharoni LM: Family unit pain history predicts child health condition in children with chronic rheumatic disease. Pediatrics. 2001, 108: E47-10.1542/peds.108.3.e47.

-

Van Slyke DA, Walker LS: Mothers' responses to boyish's hurting. Clin J Pain. 2006, 22 (4): 387-391. ten.1097/01.ajp.0000205257.80044.01.

-

Walker LS, Claar RL, Garber JL: Social consequences of children's hurting: when do they encourage symptom maintenance?. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002, 27: 689-698. x.1093/jpepsy/27.8.689.

-

Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW: Psychosocial correlates of recurrent childhood hurting: a comparison of pediatric patients with recurrent intestinal pain, organic illness, and psychiatric disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 1993, 102: 248-258.

-

Whitehead We, Crowell MD, Heller BR, Robinson JC, Schuster MM, Horn S: Modeling and reinforcement of the sick office during childhood predicts adult illness behavior. Psychosom Med. 1994, 56: 541-550.

-

Walker LS, Zeman JL: Parental response to child illness behavior. J Pediatr Psychol. 1992, 17: 49-71. 10.1093/jpepsy/17.one.49.

-

Walker LS, Williams SE, Smith CA, Garber J, Van Slyke DA, Lipani TA: Parent attention versus lark: impact on symptom complaints past children with and without chronic functional intestinal hurting. Hurting. 2006, 122 (1–ii): 43-52.

-

Branson SM, Craig KD: Children's spontaneous strategies for coping with hurting. Can J Behav Sci. 1988, 20: 402-412.

-

Dunn-Geier BJ, McGrath PJ, Rourke BP, Latter J, D'Astous J: Adolescent chronic pain: the ability to cope. Pain. 1986, 26: 23-32. 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90170-3.

-

Claar RL, Walker LS, Smith CA: Functional disability in adolescents and young adults with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: the role of academic, social, and athletic competence. J Pediatr Psychol. 1999, 24 (3): 271-280. x.1093/jpepsy/24.3.271.

-

Flor H, Birbaumer N, Rudy DC: The psychobiology of chronic pain. Adv in Behav Res and Therapy. 1990, 12: 47-84. 10.1016/0146-6402(90)90007-D.

-

Siegel LJ, Smith KE: Children's strategies for coping with pain. Pediatrician. 1989, xvi (1–ii): 110-118.

-

Connelly M, Bromberg MH, Anthony KK, Gil KM, Franks L, Schanberg LE: Emotion regulation predicts pain and functioning in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: an electronic diary study. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012, 37: 43-52. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr088.

-

Gatchel R, Peng Y, Peters Grand, Fuchs P, Turk D: The biopsychosocial arroyo to chronic pain: scientific advances and further directions. Psychol Balderdash. 2007, 133: 581-624.

-

Kashikar-Zuck S, Goldschneider KR, Powers SW, Vaught MH, Hersey AD: Depression and functional disability in chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2001, 17: 341-349. 10.1097/00002508-200112000-00009.

-

Peterson CC, Palermo TM: Parental reinforcement of recurrent hurting: the moderating touch of kid depression and feet on functional disability. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004, 29 (5): 331-341. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh037.

-

Crombez G, Bijttebier P, Eccleston C, Mascagni T, Mertens G, Goubert L, Verstraeten Chiliad: The child version of the pain catastrophizing calibration (PCS-C): a preliminary validation. Pain. 2003, 104: 639-646. 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00121-0.

-

Vervoort T, Goubert 50, Eccleston C, Bijttebier P, Crombez G: Catastrophic thinking nigh pain is independently associated with pain severity, inability, and somatic complaints in schoolhouse children and children with chronic pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006, 31 (7): 674-683.

-

Hyman PE, Bursch B, Sood M, Schwankovsky L, Cocjin J, Zeltzer LK: Visceral pain-associated disability syndrome: a descriptive assay. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002, 35: 663-668. 10.1097/00005176-200211000-00014.

-

Garralda K: Somatisation in children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1996, 37 (ane): thirteen-33. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01378.x.

-

Aaltonen One thousand, Hamalainen ML, Hoppu K: Migraine attacks and sleep in children. Cephalalgia. 2000, 20: 580-584. 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2000.00089.x.

-

Degotardi PJ, Klass ES, Rosenberg BS, Fox DG, Gallelli KA, Gottlieb BS: Development and evaluation of a cognitive-behavioral intervention for juvenile fibromyalgia. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006, 31: 714-723.

-

Huntley ED, Campo JV, Dahl RE, Lewin DS: Sleep characteristics of youth with functional intestinal pain and a salubrious comparison group. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007, 32: 938-949. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm032.

-

Long Ac, Krishnamurphy V, Palermo TM: Sleep disturbances in school-age children and chronic pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008, 33: 258-268.

-

Meltzer LJ, Mindell JA, Logan DE: Sleep patterns in adolescent females with chronic musculoskeletal hurting. Behav Sleep Med. 2005, 3: 305-314.

-

Miller VA, Palermo TM, Powers SW, Scher MS, Hershey AD: Migraine headaches and sleep disturbances in children. Headache. 2003, 43: 362-368. 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03071.x.

-

Tsai SY, Labyk SE, Richardson LP, Lentz MJ, Brandt PA, Ward TM: Cursory written report: actigraphic slumber and daytime naps in adolescent girls with chronic musculoskeletal hurting. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008, 33: 307-311.

-

Lewin DS, Dahl RE: The importance of slumber in the management of pediatric hurting. J Dev Behav Pediatrics. 1999, 20: 244-252. x.1097/00004703-199908000-00007.

-

Lautenbacher S, Kundermann B, Krieg J: Slumber deprivation and hurting perception. Sleep Med Rev. 2006, 10: 357-369. 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.08.001.

-

Roehrs T, Hyde Grand, Blaisdell B, Greenwald M, Roth T: Sleep loss and REM slumber loss are hyperalgesic. Sleep. 2006, 29: 145-151.

-

Palermo TM, Kiska R: Subjective sleep disturbances in adolescents with chronic hurting: relationship to daily functioning and quality of life. J Pain. 2005, 6 (3): 201-207.

-

Christie D, Wilson C: CBT in paediatric and adolescent health settings: a review of do-based evidence. Dev Neurorehab. 2005, 8 (4): 241-247. ten.1080/13638490500066622.

-

Jensen MP, Turner JA, Roman JM: Changing in beliefs, catastrophizing, and coping are associated with improvement in multidisciplinary pain treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001, 69 (4): 665-662.

-

Kashikar-Zuck S, Swain NF, Jones BA, Graham TB: Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral intervention for juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2005, 32 (8): 594-602.

-

Kashikar-Zuck S, Ting TV, Arnold LM, Edible bean J, Powers SW, Graham TB, Passo MH, Schikler KN, Hashkes PJ, Spalding Southward, Lynch-Hashemite kingdom of jordan AM, Banez Grand, Richards MM, Lovell DJ: A randomized clinical trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of juvenile fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 64 (ane): 297-305. 10.1002/fine art.30644.

-

Wicksell RK, Dahl J, Magnusson B, Olsson GL: Using credence and commitment therapy in the rehabilitation of an adolescent female person with chronic hurting: a case case. Cogn Behav Pract. 2005, 12: 415-423. ten.1016/S1077-7229(05)80069-0.

-

Wicksell RK, Lennart Grand, Lekander M, Olsson GL: Evaluating the effectiveness of exposure and acceptance strategies to meliorate functioning and quality of life in longstanding pediatric pain – a randomized controlled trial. Hurting. 2009, 141: 248-257. 10.1016/j.pain.2008.eleven.006.

-

Wicksell RK, Melin Fifty, Olsson GL: Exposure and acceptance in the rehabilitation of adolescents with idiopathic chronic pain – a pilot report. Eur J Pain. 2006, 11: 267-274.

-

Wicksell RK, Greco LA: Acceptance and Delivery Therapy for Pediatric Chronic Pain. Acceptance and mindfulness treatments for children and adolescents: A practitioner's guide. Edited by: Greco LA, Hayes SC. 2008, New Straw Publications, Inc, Oakland, CA, 89-113.

-

Evans S, Zelter LK: Complimentary and alternative approaches for chronic hurting. Hurting in children: a applied guide for primary intendance. Edited past: Walco GA, Goldschneider KR. 2008, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, 153-160.

-

Kohen DP, Olness K: Hypnosis and hypnotherapy with children. 2011, Routledge, New York, 4

-

Rainville P, Hofbauer RK, Bushnell MC, Duncan GH, Price DD: Hypnosis modulates activity in brain structures involved in the regulation of consciousness. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002, 14: 887-901. 10.1162/089892902760191117.

-

Vlieger AM, Menko-Frankenhuis C, Wolfkamp SCS, Tromp E, Benninga MA: Hypnotherapy for children with functional abdominal hurting or irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2007, 133 (5): 1430-1436. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.072.

-

Anthony KK, Schanberg LE: Pediatric pain syndromes and direction of pain in children and adolescents with rheumatic affliction. Pediatr Clin of North Am. 2005, 52 (2): 611-639. 10.1016/j.pcl.2005.01.003.

-

Carter BD, Kronenberger WG, Edwards JF, Marshall GS, Schikler KN, Causey DL: Psychological symptoms in chronic fatigue and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatrics. 1999, 103 (5): 975-979. 10.1542/peds.103.5.975.

-

Brace MJ, Smith MS, McCauley E, Sherry DD: Family unit reinforcement of illness behavior: a comparison of adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome, juvenile arthritis, and salubrious controls. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2000, 21: 332-339. ten.1097/00004703-200010000-00003.

-

Wright B, Ashby B, Beverley D, Calvert East, Jordan J, Miles J, Russell I, Williams C: A feasibility study comparison 2 treatment approaches for chronic fatigue syndrome in adolescents. Arch Dis Child. 2005, 90: 369-372. x.1136/adc.2003.046649.

-

Garralda Thousand, Chandler T: Practitioner review: chronic fatigue syndrome in childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005, 46 (11): 1143-1151. ten.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01424.x.

-

Viner R, Gregorowski C, Vino G, Bladen D, Fisher M, Miller M, El Neil S: Outpatient rehabilitative treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS/ME). Arch Dis Child. 2004, 2004 (89): 615-619.

-

Logan DE, Simons LE, Stein MJ, Chastain Fifty: School impairment in adolescents with chronic pain. J Pain. 2008, ix (5): 407-416. ten.1016/j.jpain.2007.12.003.

-

Kashikar-Zuck South, Parkins IS, Ting Telly, Verkamp Eastward, Lynch-Jordan A, Passo M, Graham TB: Controlled follow-up written report of concrete and psychosocial operation of adolescents with juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome. Rheumatol. 2010, 49: 2204-2209. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq254.

-

Long Air-conditioning, Krishnamurthy V, Palermo TM: Sleep disturbances in schoolhouse-age children with chronic pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008, 33 (3): 258-268.

-

Bruni O, Galli F, Guidetti V: Slumber hygiene and migraine in children and adolescents. Cephalalgia. 1999, 19 (Suppl 25): 57-59.

-

Palermo T, Eccleston C, Lewandowski Equally, Williams A, Morley S: Randomized controlled trials of psychological therapies for management of chronic hurting in children and adolescents: an updated meta-analytic review. Hurting. 2010, 148: 387-397. x.1016/j.pain.2009.10.004.

-

Carter BD, Kronenberger W, Sherman Grand, Threlkeld B: Clinical Outcomes of a Manualized Treatment for Adolescents with Chronic Pain and Fatigue. Paper presented at: The Society of Pediatric Psychology Midwest Regional Conference. Apr 2012, , Milwaukee

-

Hechler T, Blankenburg M, Dobe M, Kosfelder J, Hubner B, Zernikow B: Effectiveness of a multimodal inpatient treatment for pediatric chronic pain: a comparison between children and adolescents. European J Hurting. 2010, 14: 97-e1–97.e9

-

Nijhof SL, Bleijenberg G, Uiterwaal C, Kimpen J: Effectiveness of net-based cognitive behavioural treatment for adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome (FITNET): a randomised controlled trial [published online ahead of print March 1, 2012]. Lancet. 2012

Acknowledgements

Dr. Carter's research on CHIRP was supported past Grants Number #28-9 and #2011-7, titled, "Characterization and Treatment of Adolescents with Fatiguing and Painful Medical Weather condition as seen in CHIRP (Children'south Wellness & Affliction Recovery Programme)" (Bryan D. Carter, Ph.D., PI) from the James R. Petersdorf Fund of Norton Healthcare, Inc.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they take no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

BC literature review and manuscript preparation. BT literature review and manuscript preparation. Both authors read and canonical the terminal manuscript.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Carter, B.D., Threlkeld, B.M. Psychosocial perspectives in the handling of pediatric chronic pain. Pediatr Rheumatol 10, 15 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-10-15

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-10-15

Keywords

- Chronic pain

- Children

- Adolescents

- Psychosocial

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

Source: https://ped-rheum.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1546-0096-10-15

0 Response to "What Are Some Negative Effects That Chronic Pain Can Have on the Pediatric Population?"

Post a Comment