What’s wrong with the Vergara ruling

Credit: Claremont Graduate University

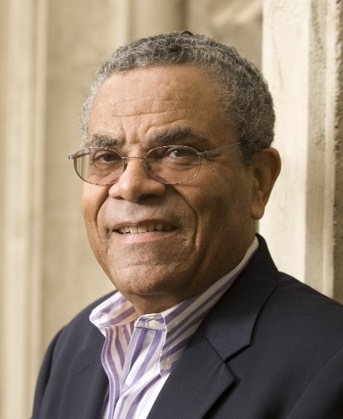

Carl Cohn

Credit: Claremont Graduate Academy

Credit: Claremont Graduate Academy

Carl Cohn

Virtually two decades ago, when I was superintendent in the Long Beach Unified School District, the superintendent in nearby Palos Verdes asked me if he could transport some of his teachers to our workshops to help them improve their skills in didactics kids how to read.

I wondered why one of the state's wealthiest and most successful districts, at least as measured by its test scores, would want to send its teachers to acquire skills from an urban district like ours, with test scores that were far lower.

When I looked at the superintendent with a puzzled expression, he said: "If most of our kids didn't come to our schools already knowing how to read and write, we'd be exposed for the frauds that we are."

This superintendent implicitly acknowledged what isn't often known by the general public: Teachers at suburban school districts like the one in Palos Verdes have to do far less for their students to get loftier test scores than those at urban school districts similar mine.

I was reminded of that conversation after the recent ruling in the Vergara lawsuit that declared several key laws governing instructor employment unconstitutional under California law. What's incorrect with the ruling is that it reinforces a completely false narrative in which incompetent teachers are portrayed as the primal problem facing urban schools.

Serving equally superintendent in both Long Beach and San Diego for 12-plus years, I didn't come across the "teacher jails" or "safety rooms" – the places where teachers are assigned and do nothing while whatsoever of a range of charges against them are adjudicated – that have become a office of the popular-media-driven narrative well-nigh urban schools and districts.

I saw remarkably heroic classroom teachers who delivered high-quality instruction on a daily ground. Sure, there were times when a instructor wasn't performing up to par and needed assist. And yes, there were times when a teacher needed to observe a new career. Simply the notion that the only selection facing an urban district is to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars removing such teachers says more about poor leadership and poor homo uppercase management in that commune than information technology does most the existing state statutes under consideration in this court case.

In my experience at Long Beach, the biggest assist in counseling a teacher toward finding a new career was the head of the local teachers union, who understood that keeping a sub-par instructor in the profession was bad for both the district and the marriage. Almost of the heavy lifting on getting that resignation was washed by the union, not the district.

In recent years, it has become fashionable to advise that the battle in urban districts is all well-nigh adult interests versus the interests of schoolchildren. The truth is that an constructive leader of an urban school organization goes to work every mean solar day trying to figure out how best to motivate, inspire and develop the adults who piece of work with kids. Those superintendents who feel that they tin can transform kids' lives by fiat from the superintendent'south suite are kidding themselves and fooling the public. Enlisting, engaging and collaborating with classroom teachers are the only ways to genuinely move the needle on student achievement.

In California, there are simply 2 districts that have won the prestigious Broad Prize for Urban Education. Both Long Embankment and Garden Grove accomplished that feat past bringing a laser-like focus to improving the capacity of their teachers through high-quality professional development, and using data to target kids who are behind. Neither district chose the path of firing their mode to excellence or denying their teachers their hard-won due-process rights. And, I might add, neither district saw gimmicks similar iPads every bit the formula for educational excellence.

The Vergara ruling as well addresses the twin bug of layoff procedures and length of fourth dimension needed to proceeds tenure.

I teach a course at Claremont Graduate University called "Strategic Direction of Human Capital in High-Performing Districts." My doctoral students e'er go into that class thinking that changing the current system of layoffs based on seniority would be an easily accomplished reform. However, after several hours of discussion, most readily acknowledge that hardworking teachers may all the same need to be protected from political retribution from some school administrators who might corruption the system to punish teachers who practice their correct to free speech by criticizing the actions of administrators, or who have become an economical burden during price-witting budget-cut times. Though current laws regarding teacher tenure are admittedly imperfect, repealing them, in my judgment, might subject field teachers and the students we care about to fifty-fifty greater anarchy and defoliation.

When I arrived in San Diego in 2005, ane specially disturbing access came from ane of the district's area superintendents. She indicated that she had transferred an excellent elementary instructor from her inner-urban center school because the teacher had exercised her complimentary speech rights in disagreeing with the summit-down nature of the previous superintendent's "Blueprint for Student Success." The transfer, however, did non silence the teacher. But the contrary, in fact. The next year, she was elected president of the San Diego teachers spousal relationship.

Proponents of abrogating the rights of teachers often fence that incidents like this 1 in San Diego were common decades ago, but no longer happen today. My feel tells me that they are wrong on that score.

Some change may well need to exist considered in the length of time teachers must serve before gaining tenure. Virtually observers are waiting for some grand bargain to be crafted at the state level. But I call back this would be all-time done from the "lesser up" in urban districts like San Jose and others, where district and marriage leaders are coming to the same conclusion that some beginning teachers are meliorate served by lengthening the probationary period. State leaders and CTA need to get out of the mode and let this happen.

The piece of work of improving urban schools is a long, hard slog. It requires stability of leadership and governance, forth with taking the time to develop common trust between administrators and unions on building the chapters of the vast majority of the teacher workforce. Unfortunately, there are no shortcuts.

California is a slap-up state that should never consider turning back the clock either on the civil rights of urban students, who have the correct to a high-quality public schoolhouse education, or on the employment rights of the dedicated teachers who I saw serving them so well in both Long Beach and San Diego.

•••

Carl Cohn, quondam school superintendent in Long Beach and San Diego, is director of the Urban Leadership Program at Claremont Graduate University and a fellow member of the State Lath of Education. He is also chair of the American College Testing (ACT) Lath of Directors, and a member of the EdSource Board of Directors.

The opinions expressed in this commentary correspond solely those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please contact us.

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource'south no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.

Source: https://edsource.org/2014/whats-wrong-with-the-vergara-ruling/68077

0 Response to "What’s wrong with the Vergara ruling"

Post a Comment